It is unlikely that many of you will recall what hot metal typesetting was all about. Imagine a huge typewriter with a heater attached that melts metal to be cast into lines of type. This was called a “linotype” machine (from “line-o’-type”, believe it or not). A few still remain. The linotype machine operator enters text and the machine assembles matrices, which are patterns for the letter forms, in a line. The assembled line is then cast as a single piece, called a slug, from the molten metal. The metal is a complex alloy of lead, and this process is known as hot metal typesetting.

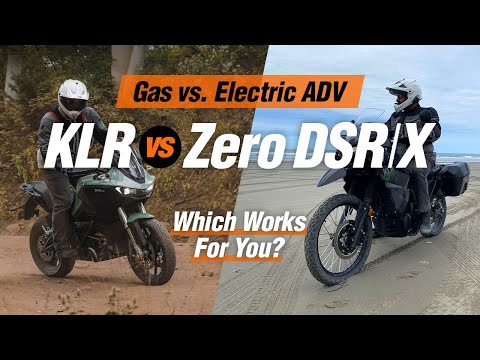

Ride one of these today and you’ll be staggered how underpowered they are. Photo: The Bear

Computers have made such Heath Robinson devices redundant, but it was linotype machines that made newspapers as we know them and much other printing possible. Because the machines were expensive and the work skilled, most printers relied on typesetting services. One such in Sydney was called Wallace & Knox, and I worked for them for a while as a delivery rider, using a WLA Harley-Davidson with a side box, very much like the one in the photos.

One Saturday morning I got a call from Vince, the foreman. Could I come in? It seemed that the Mini van had a problem and couldn’t complete its run. Of course I could come in. I’d be getting paid time and a half.

Basic is an understatement. The chrome switch below the speedo is the ignition switch. Right filler cap is for oil, left for fuel. Do not mix them up. Can you work out why? Photo: The Bear

Saturday morning was a special time in the typesetting business. All through the week, we would be taking made-up advertisements, most of them full pages, to the newspaper printers. These were for the Sunday papers, which always carried staggering numbers of ads. The ads were fully made up, which means that the body type, headlines and images were locked into steel frames called formes, ready to be transferred to flongs, a kind of papier mâché mould which was then used to cast the final type for printing. This was done during the week, and by Saturday morning the newspapers no longer needed our formes. They weren’t used in the actual printing, after all. Printer’s metal was valuable, so the firm’s Mini van would be despatched to collect all of the used formes to return them to the typesetter’s.

Only in this case, the weight had been too much and the van had snapped its spine. Wallace & Knox had two outfits, and they would have to do the van’s work. But Tom, who rode the other outfit, was not to be found. He’d been out in the country (something we were not supposed to do with the outfits), and when he came in on Monday he performed his usual little ritual. He whacked his extended left hand with his right and cried: “Smacks for Tom!” But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Available torque meant that three gears were quite enough. Some bikes had reverse, too. Photo: The Bear

Maybe I could do the run in two or three goes, suggested Vince. Well, I thought, maybe I can. Let’s see.

The despatch bloke at the Sun-Herald printery was pretty keen to get all of the metal out of his loading dock. It was bad enough having to load the Mini and then unload it again when its belly suddenly headed for the ground. He wanted all that stuff out of there, and now. I looked at the potential load and worked out that it would only just fill the sidecar box, so I got him to help me slide the entire load aboard.

“You sure about this?” he asked when we were tucking the last few formes in.

“Why?” I said.

“Well,” he replied, leaning over to read the weigbridge ticket, “the metal’s just over a tonne…”

“She’ll be right,” I said. After all, nobody had ever established a permissible maximum load weight for the bike. Time to do that! The tubular frame of the sidecar was immensely strong, and the fittings holding it to the bike would have held, at a guess, the average frigate. I will, however, admit that I wasn’t entirely sure the bike was going to make the trip…

The left handgrip is used to advance or retard the ignition. Tricky if you don’t know it! Photo: The Bear

I still doubt that I would have got up much of any kind of hill, but if you went the right way there was no significant uphill section between the Sun-Herald and Wallace & Knox. All you needed to do was take a stretch of one-way road the wrong way, which was no problem because who was going to stop me?

WLAs have three gears, and I did not get out of first, but I made it while the clutch got quite a workout. Mind you, if I’d hit a pothole with the sidecar wheel, I’m pretty sure I would suddenly have been on a solo… even that herculean frame would have given way. Vince was visibly impressed when I arrived at our loading dock.

Best job I ever had, really. Along with hot metal typesetting, the Wallace & Knox outfits are part of history now. I hope they’re not forgotten. I suppose I should be grateful that I’m still around.