When the talk turns to motorcycles someone used to own, the questions usually revolve around the bike itself. Did you like it, how did it go, did it have any faults… and so on. In the case of the Silk 700S, the first question (or possibly the second, after “What’s a Silk 700S?”) is “Why did you sell it?”

In case you’re not familiar with the bike yourself, here’s a quick rundown of this elegant and ever-stylish machine.

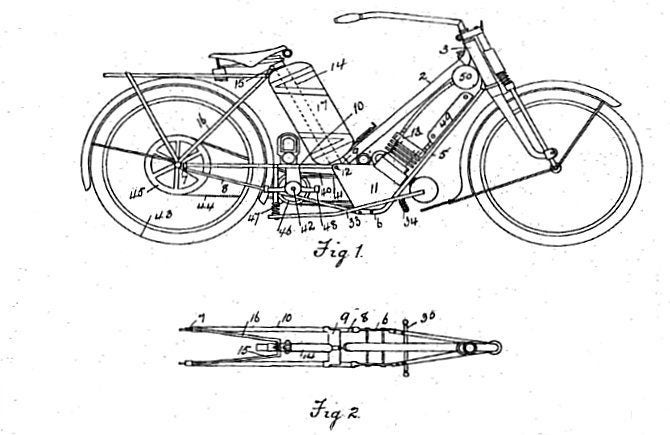

The first patent drawing of the bike that would become the Scott Squirrel.

We need to go back to 1908 and the northern English town of Shipley to trace the Silk’s origin, when Alfred Angus Scott designed the liquid-cooled two-stroke twin back in 1908. In 1897, he had started working on a 2 hp standing 2-cylinder 2-stroke engine, which was built into a Premier bicycle. He continued to develop the engine, and patented a vertical-twin, two-stroke engine design in 1904. In 1908 the first six Scott motorcycles, powered by a 450 cc two-stroke, twin-cylinder, water-cooled engine and completely designed by Alfred, were built by the brothers William and Benjamin Jowett. They featured a patented two-speed chain transmission, in which the ratios were selected by clutches, operated by a rocking foot pedal. This bike also had a patented kick-starter. These bikes were effectively prototypes before Scott officially appeared on the market as a brand.

Buyers could have the bikes in any color they liked. The red looks good, I think. Photo: The Bear

The first public appearance of a Scott was in a hill climb in July of 1908, and there seems to be no record of the results. In the second outing for the bike at the 1908 Wass Bank hill climb, a few weeks later, it won three classes: the open, twin cylinder and variable transmission classes. Scott’s motorcycles were powerful enough to beat four-stroke motorcycles of the same capacity with ease. The first of many protests that would follow Scott’s bikes sounded immediately, and the Auto-Cycle Union handicapped Scott motorcycles by multiplying their cubic capacity by 1.32 for competitive purposes. That resulted in a lot of free advertising for Scott.

The bike’s stance is remarkably modern with its clip-on handlebars. Photo: The Bear

Racing success followed, but WW1 interrupted development and Alfred Scott left the company after the war. Then, in 1922, the company introduced the first of the famous “Squirrel” sporting models, but its fortunes waxed and waned until the late 1970s when then-owner Matt Holder finally closed it.

In the meantime, however, George Silk, a Scott motorcycle enthusiast who worked for Derbyshire Scott specialist Tom Ward, had developed a race bike by fitting a Scott engine into a modern Spondon frame. He made 21 or 22 of these before he ran out of engines and Holder prevented him from building more. George Silk countered by developing a 653 cc water-cooled parallel twin motor in conjunction with engineers from Rolls Royce and Queen’s University Belfast. Launched in 1975 with a price tag of £1355, it powered one of the most expensive motorcycles in the world and was hand built at the rate of two a week. As well as the beautiful steel tubular frame, chassis specialist Spondon Engineering also produced the forks and brake components.

That temperature gauge is by far the most important of the instruments. Photo: The Bear

Contemporary reports complimented the 700S on its sweet handling, something I can vouch for myself. With its 18-inch wheels front and back, braked by a 254mm front disc with twin piston caliper and a 180 mm drum rear and weighing a mere 309 lb dry, the 700S is probably the best-handling bike I have ever owned – possibly even the best I have ever ridden. The all-aluminum two-stroke engine, even though it was visually similar to Scott’s 60-year-old Squirrel design, backed up the handling and made the bike a formidable road machine. Power from the piston ported engine, at least on the later bikes like mine, was a respectable 54 hp. A single 32 mm Amal carb and two-into-one expansion chamber from Ossa in Spain also boosted bottom-end drive. Peak torque came in at just 3000rpm. The engine was good for a claimed top speed of 111 mph, although the machine was handicapped by the widely spaced four-speed gearbox, repurposed from the 1950s Velocette Venom and fitted upside-down. I never got mine up to anywhere near 100 because I was afraid of seizing it at speed. The final drive chain was enclosed for longer life. Why don’t all chain bikes have this?

I wonder what happened to the bike? A collector bought it, no doubt. Photo: The Bear

The Silk was exceptionally well lubricated with a 50:1 petroil premix, but it also had a huge separate oil tank for main-bearing lubrication, linked to the throttle. Open the throttle and the oil flowed faster. Another quirky touch was the petrol tap located behind one of the side panels, which had to be removed to switch onto reserve. And then there was the cooling system. The engine had no water pump, using instead a thermo-syphon cooling system. Coolant in the cylinder jackets absorbed engine heat and rose convectively via a rubber tube to the radiator. The cooled liquid was denser and returned through another tube to the base of the cylinders.

And there we have the answer to that question. I sold my Silk 700S because the cooling system simply didn’t work. Even in winter, I was constantly aware of the likelihood of seizing the engine and in fact managed to do just that a few times. I don’t keep bikes I can’t ride, so I sold it. One of 138 made, beautiful and a joy to ride, but finally… useless.